Journalists, researchers, and politicians are expressing growing concern over Meta’s decision to shut down CrowdTangle, a tool they heavily relied on to track the spread of disinformation across Facebook and Instagram. For many, CrowdTangle was more than just a tool—it was a critical resource in the fight against misinformation.

In place of CrowdTangle, Meta is now offering its Content Library, a tool that’s raising eyebrows for all the wrong reasons. Unlike CrowdTangle, which was widely accessible, Meta has restricted access to the Content Library to individuals from “qualified academic or nonprofit institutions engaged in scientific or public interest research.” This means many researchers, academics, and most notably, journalists, are being left out in the cold.

Those who have managed to get their hands on the Meta Content Library report that it falls significantly short in terms of transparency, accessibility, features, and user experience. Many in the community have voiced their discontent, writing open letters to Meta and questioning why the company would retire such a vital tool just three months before one of the most contentious U.S. elections in history. The timing has sparked outrage, especially as the upcoming election is already threatened by AI-generated deep fakes and chatbot misinformation—some of which has originated from Meta’s own platforms.

So, why fix what wasn’t broken?

Meta has provided few answers. At an MIT Technology Review conference in May, Meta’s president of global affairs, Nick Clegg, defended the decision, calling CrowdTangle a “degrading tool” that didn’t provide complete or accurate insights into what’s happening on Facebook.

“It only measures a narrow cake slice of a cake slice, which is particular forms of engagement,” Clegg argued. “It literally doesn’t tell you what people are seeing online.”

Clegg’s harsh critique of CrowdTangle paints it as almost recklessly inadequate, a stark contrast to Meta’s previous endorsement of the platform in 2020. Back then, Meta promoted CrowdTangle as a crucial resource for Secretaries of State and election boards across the country, helping them “quickly identify misinformation, voter interference, and suppression.” The platform even allowed users to create custom “public Live Displays for each state” to monitor real-time data.

Today, Meta’s stance is that the Content Library offers more detailed insights into what people actually see and experience on Facebook and Instagram. A Meta that the new tools provide a more comprehensive data-gathering experience.

However, this explanation hasn’t convinced everyone.

Cameron Hickey, CEO of the National Conference on Citizenship, is one of the critics. He argues that the Meta Content Library offers only “10% of the usability of CrowdTangle.” Hickey explains that CrowdTangle was initially “a sophisticated quasi-commercial product” before Facebook acquired it in 2016. Under Facebook, the tool improved as the team incorporated feature recommendations from a large and diverse user base.

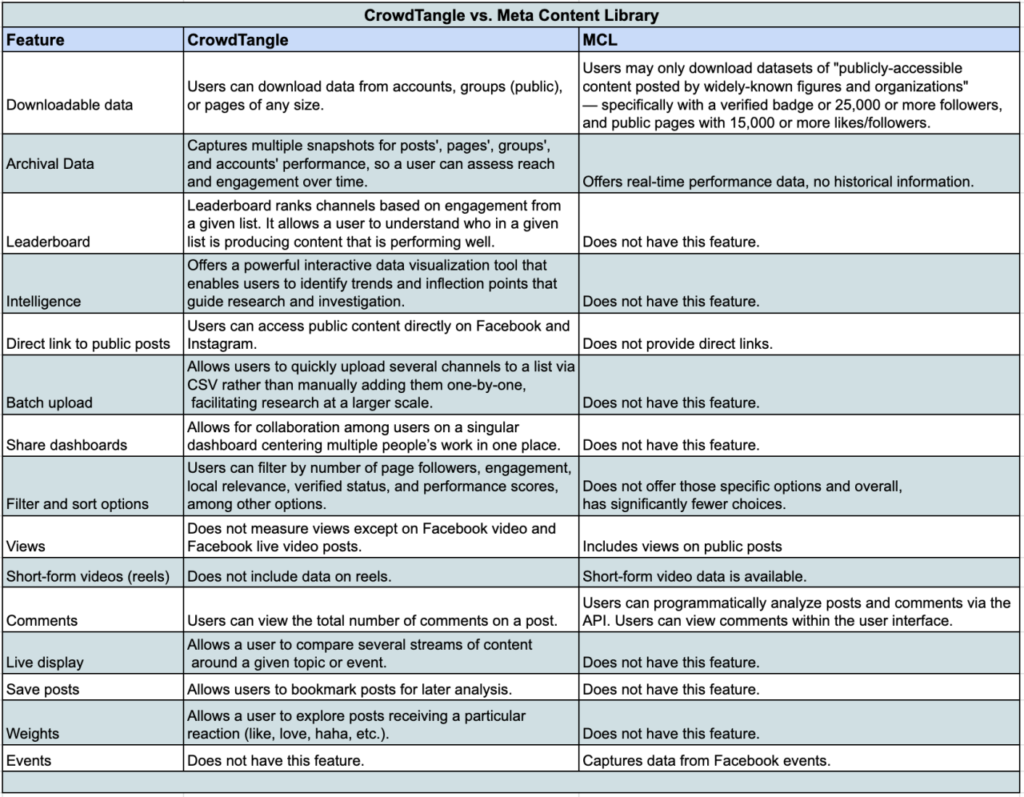

Hickey co-authored a report comparing the features of CrowdTangle and the Meta Content Library, published by Proof News and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia’s Journalism School. His conclusion? Meta’s new tool offers only “1% of the features” that CrowdTangle provided.

“For instance, if you wanted to track the number of followers on CNN’s Facebook page over time, that’s something you can’t do with the Meta Content Library, but you could with CrowdTangle,” Hickey noted. “Metrics like these are crucial for understanding how the prominence of a social media actor changes over time and how it correlates with events like a viral post that causes their follower count to spike.”

Even features that exist across both platforms, such as tracking political party posts and comparing their relative engagement, are more cumbersome in the Content Library. This, Hickey argues, points to poor user experience design.

Perhaps the most significant limitation is what users can do with the data. While you might be able to access information about posts mentioning a topic like immigration, your ability to analyze that data is severely restricted.

“You can’t build interactive charts like you could with CrowdTangle,” Hickey said. “You can’t create public dashboards. And most importantly, you can’t download all of the posts.”

Users can only download posts from accounts with more than 25,000 followers—a threshold that excludes many politicians. This restriction leaves researchers with limited options, one of which is the problematic and often legally dubious practice of scraping data directly.

Another major issue is that Meta is not granting access to watchdogs that previously used CrowdTangle to monitor the spread of misinformation. Media Matters, a nonprofit watchdog organization, is one such example. The group doesn’t have access to the Content Library today, even though it previously used CrowdTangle to debunk claims from right-wing media and Republican talking points that Facebook was censoring conservative content. In fact, Media Matters’ research showed that right-leaning pages received significantly more engagement than non-aligned or left-leaning pages.

“CrowdTangle allowed us to see what kind of content was widely engaged with on the platform,” said Kayla Gogarty, research director at Media Matters. “Algorithms are usually a black box, but at least some of that engagement data helped us understand the algorithms better.”

Gogarty pointed out that ahead of the January 6 attack on Capitol Hill, researchers and reporters used CrowdTangle to sound the alarm about online organizing and the potential for violence aimed at delegitimizing the election.

“What this ultimately means is that fewer civil society groups will be able to monitor and track what’s happening on Facebook and Instagram during this election year,” warned Brandi Geurkink, executive director of the Coalition for Independent Technology Research.

Hickey also contrasted Meta’s actions with those of Elon Musk at Twitter (now X). When Musk acquired Twitter, he immediately restricted access to the Twitter API, which allowed developers, journalists, and researchers to access and analyze data from the platform similarly to how CrowdTangle functioned. Now, the cheapest enterprise API package on X costs $42,000 a month, and it only provides access to 50 million posts.

In summary, Meta’s decision to retire CrowdTangle has raised significant concerns, especially with the 2024 U.S. elections on the horizon. The new Content Library, while more advanced in some respects, falls short of the functionality and accessibility that CrowdTangle provided. For those dedicated to tracking misinformation and ensuring electoral integrity, the loss of CrowdTangle feels like a step backward at a time when the stakes couldn’t be higher.