There comes a time in every startup’s life when leaders and stakeholders have to seriously start thinking about the endgame: What do you do when you’ve raised $150 million in VC cash over 15 years en route to building a 100 million-plus community? And how do you go about executing that next step to ensure that you not only survive but also thrive?

This is the predicament that Strava, the social fitness app and community, finds itself in. It’s at a crossroads, of sorts, having reached meaningful scale driven by the grit typical of many founder-led businesses, but now hitting an impasse in scaling further.

“What got us here will not be exactly the same as what will get us there,” Michael Horvath, Strava co-founder and then-CEO, said as he announced his imminent departure in February 2023. “I have decided that Strava needs a CEO with the experience and skills to help us make the most of this next chapter.”

That next chapter started in January when Strava announced that its new CEO would be former YouTube executive and Nike digital product lead Michael Martin. Six months into his new role, Martin has already given the first clues as to where his head is in terms of both business and product, revealing plans to use AI to weed out leaderboard cheats, as well as new features to broaden its demographics.

Over the past few weeks, Strava also introduced a new group subscription plan, while it finally gave its users the feature they’ve been asking for more than any other: dark mode, a glaring omission that had frustrated many through the years.

For context, YouTube has had dark mode since 2018; X (formerly Twitter) since 2019; and everything from WhatsApp to GitHub has long offered dark mode, too.

“If you were to build the Strava app now, or even in the last two or three years, turning on dark mode would have been very straightforward,” “But Strava is not a new app.”

As the Strava app has evolved over the past 15 years, it has been added to, layered upon, and cobbled in a less-than-congruous fashion that made it difficult to introduce what, to the outside world, would seem like a fairly simple update.

“Instead of flipping a switch, it was the exact opposite,” Martin said. “There were hundreds of screens that had to be updated, thousands of UX (user experience) controls, each one of them individually coded. And so it took far more work than people would assume, but I understand why you would think it would be an easy thing.”

For dark mode to happen, Strava overhauled the user interfaces to adhere to a more “modern, modular” ethos. “Honestly, dark mode is just a nice benefit of doing all that additional work,” Martin said. “Going forward, every feature will be faster.”

While it may have been a hotly anticipated feature, dark mode is the least of Strava’s concerns. It’s a nice-to-have, but it won’t make or break the business. TechCrunch sat down with Strava’s new CEO in London for a wide-ranging interview, delving into what the company is prioritizing and what we can expect in the future as the company embarks on its “next chapter.”

“Our product development is finely focused on two things right now,” Martin explained. “‘Building for her,’ which is really just our lens for making sure that we are doing everything to make Strava more inclusive. And the other is AI and machine learning.”

Building for Her

Strava doesn’t reveal its gender split, but Martin acknowledged that its user base follows a trend that permeates much of the sporting realm. “Participation rates for women have always substantially lagged men [on Strava],” Martin said. “I think Strava has a unique opportunity to help women be more active and engage in more activities.”

There are encouraging signs in some demographics, according to Martin, who pointed to markets like the U.K., France, and Spain, which are apparently seeing new user registration rates for women exceed 50% of the whole new user base. However, he said that the growth rate of Gen Z female users in the U.K. has doubled in the past six months compared to the previous six months.

“So you can start to understand that even if women were less prominent on the platform, that’s starting to shift pretty profoundly, which is what we want to happen,” Martin said.

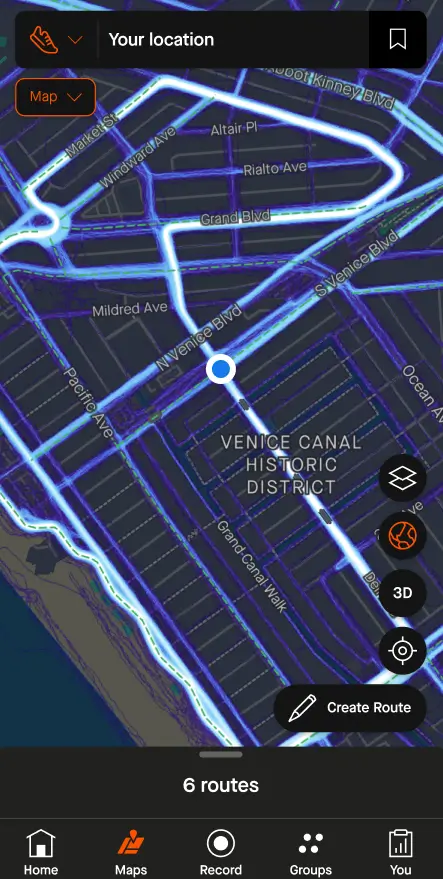

One way Strava hopes to broaden its appeal is through a feature that builds on its existing global heatmaps, which showcase the most well-trafficked running, riding, and walking routes. With the soon-to-launch “night heatmaps,” this highlights the busier routes between sundown and sunrise specifically.

Additionally, Strava is working on ways to make it easier to conceal specific data points from an activity, which might be useful for those concerned about being monitored. “Quick edit” will enable users to hide certain metrics from their stats, such as their location or activity type.

“It’s a mechanism that I learned at Google as a way to find those gaps in the product,” Martin said. “Addressing these gaps ideally will help ‘her’ be more active. And we’re already seeing that in the numbers. This is going to help other people as well; it’s an inclusive design.”

The AI Factor

Besides identifying gaps in the existing product, Martin says he’s looking to borrow from other recent experiences at Google, where he says AI and machine learning were part of just about everything they did.

“I’d been working in machine learning and artificial intelligence for almost a decade already, but spending the last couple of years at Google gave me a whole new level of understanding and capability, which I am now employing at Strava,” Martin said. “And you’re going to see more examples of that going forward.”

Strava recently announced it would use more sophisticated machine learning to detect “leaderboard cheats.” The Leaderboard is a Strava feature that stirs competition by allowing users to challenge each other over certain “segments” of a route. While most people tackle these segments fairly, accusations frequently abound that some use nefarious methods to beat a particular record, perhaps using a pedal bike on a “run” or an e-bike on an ascent.

It’s a major bone of contention in the community, one that led Strava to allow users to manually flag dubious activity, while last year the company updated its algorithms to make “leaderboards more credible.” This included withholding activities that may have been incorrectly labeled (e.g., users tagging a run as a bike ride) or maybe where the GPS data was faulty.

Moving forward, Strava will use machine learning to detect questionable activities trained on historical data. But much like dark mode, Martin says that weeding out digital dopers is easier said than done.

“As somebody who has been an engineer at many points in my career, I feel like I can imagine a heuristic, an algorithm that can solve for this [leaderboard integrity] relatively easily,” Martin said. “In reality, you could, and the team has tried that in the past, but what they have come to realize is that while you can create a heuristic, those heuristics have consistent failings in terms of incorrectly flagging anomalous behavior that isn’t actually anomalous.”

This is where Martin hopes machine learning can help: by spotting connections and patterns that a human being creating a “hypothetical heuristic” would never imagine including in their design.

Details of what this might look like remain somewhat vague, but when pushed on whether Strava might become more effective at detecting someone using an e-bike to ascend a hill, for example, Martin was optimistic but noncommittal.

“I think there’s a high probability, but I don’t want to overstate,” Martin said.

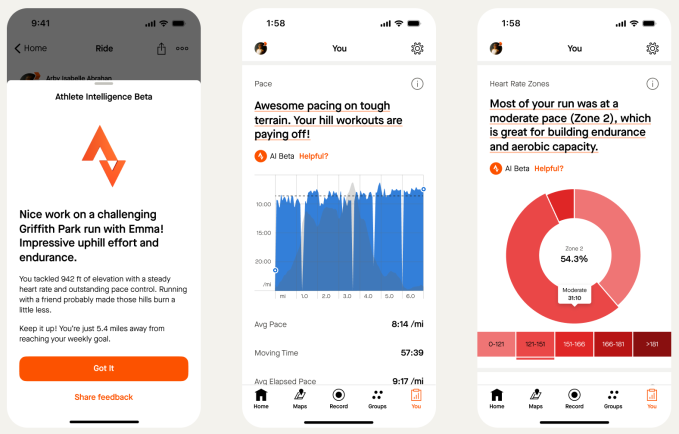

While Strava already serves up performance data and insights, the company is also turning to AI to make this data easier to parse, particularly for newbies. An upcoming feature called “athlete intelligence” will see Strava deploy generative AI to analyze user data and create summaries and guidance on performance and fitness goals. This will be available to premium subscribers only.

“Athlete intelligence is a way of using AI to solve a specific human problem; it can take their data and give them specific contextual information,” Martin said. This might include things like contextualizing a particular segment of a run in terms of how their pace relates to an incline, or explaining how their heart rate over a given period translates into building endurance.

The Social Network

While Strava isn’t typically bundled alongside traditional social networks like Facebook, the platform is very much used like a social network, with the ability to share photos, and videos, comment on activities, and, as of last year, send private messages. The company refers to itself as a “social network specifically for active people.”

However, Martin sees things slightly differently. “Strava’s a ‘social product,’” he said. “[But] the point of a social media network is that the whole thing is optimized to maximize your engagement in that network. Strava is optimized and focused on exactly the opposite. Our goal is to motivate you to do something in the real world, not to stay in Strava all the time. The average Strava consumer spends 20 times more in the real world in an activity than they do in the app. And I think that’s a super healthy stat. I’m not looking to change that.”

There are other synergies with traditional social networks, too, and not necessarily positive ones. Strava has always been about the data, whether it’s a runner viewing their marathon splits or a cyclist tracking their segment improvements. When pooled, this data could hold immense value for any company wishing to diversify their revenue streams beyond subscriptions. But this is something Strava has been at pains to control the optics around, particularly against the backdrop of Big Tech companies such as Facebook misusing user data.

Strava’s main data product is packaged under something called Strava Metro, where it shares aggregate, de-identified data with select city planners, governments, and organizations to improve infrastructure. So if Strava data shows that a lot of people are cycling along a particularly busy thoroughfare, it might warrant investment in bike lanes. Strava used to charge for this product, but in 2020 it made the tool available for free, an effort designed to showcase its “good guy” credentials, while also underscoring its main business model as subscriptions.

“Strava had already declared that it was not looking to monetize the data of the community,” Martin said. “And so I honor that commitment. One of the reasons I love the subscription business model for a fitness product is it makes it really clear it’s the subscription that’s the product, not your data.”

But things get a little murky when you look at Strava’s privacy policy, which is quite clear in how it might leverage user data. While it explicitly says that it won’t sell users’ personal information for “monetary value,” it may “use, sell, license, and share” aggregate information with third parties for “research, business or other purposes” (though users can opt out).

In a follow-up question to clarify whether Strava does or doesn’t sell aggregate user data as its privacy policy seemingly permits it to do, the company said that it doesn’t and has no plans to do so, saying: “Strava’s legal notices are designed to address privacy laws, regulations, and compliance standards in all its global markets. Given that some regions take an expansive view of terms such as ‘sell’ (and include within the definition activities where no money is exchanged), Strava has opted to mirror that term in order to increase transparency and support differing definitions globally.”

The company also said that it intends to update the wording of its policy to reflect the fact that it doesn’t sell any of its data — aggregate or otherwise — for “monetary value.”

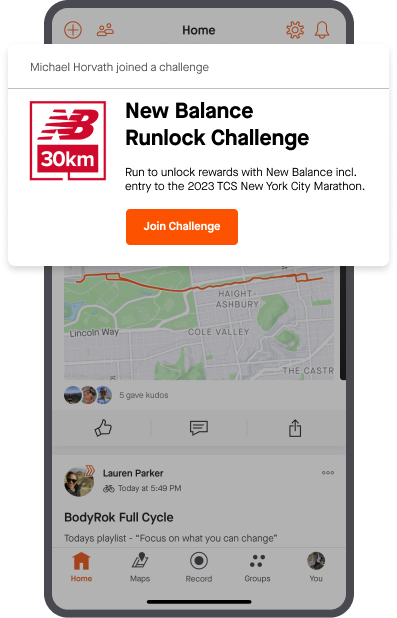

It is worth noting, however, that Strava also offers a business product where brands can pay to sponsor a particular challenge, with the option to target users by sport type, location, and certain demographics. So yeah, the company does use data as part of its targeted advertising efforts.

The Future for Strava

Whenever a new leader lands in the hot seat — particularly at a company with such a fervent online community — this can lead to all manner of speculation about why that person was chosen, what skills they have for the job, and more importantly, what direction they’ll take things in.

In the case of Strava, why did it hire someone who most recently worked on YouTube’s shopping business? To the casual observer, the synergies were not immediately obvious, sparking some to pontificate that this might signal a new direction for Strava, perhaps with advertising driving revenue.

“Just to be direct, I’m not looking to make Strava an advertising product,” Martin confirmed. “YouTube is one of the largest advertising products in the world, and they do a great job of that. But that’s not the right approach for Strava. I believe subscription is the right model for Strava.”

So what does Martin hope to bring to Strava from his time at Google’s video-streaming subsidiary? “It’s about building to scale — and YouTube is one of the most scaled products in the world,” Martin said. “It’s about not only understanding what it means to build to that level, but also understanding what it means to build new things within that level.”

And then there are other prior experiences, both in a professional and personal capacity, that Martin says meant he was able to hit the ground running in many regards. “I’ve been a member of the Strava community, and a subscriber, for more than seven years — so I’m quite familiar with the product from the consumer side,” he said. “I’ve also worked in the fitness tech space before, I spent time at Nike running competing products. So I understand the area. When you look at my track record, what I’ve done in these different areas of tech is that I’ve either launched new products from zero or I’ve taken products to substantially higher scale.”

Most VC-backed technology companies reach some sort of exit within a decade of their foundation, whether that’s an acquisition or IPO. Reddit was an outlier when it went public this year after 19 years, and Strava finds itself in something of a similar position: a veteran of the technology realm, with no obvious exit in sight.

But what seems clear from all the product activity over the past six months is that Strava is trying to build something that will reach its full potential one way or another. In support, Martin recently brought on two seasoned veterans in the form of new CTO Rob Terrell from Zynga and Epic Games’ Matt Salazar as chief product officer.

“Six months in, my focus right now — I think understandably — is narrow,” Martin said. “The investors are all very much aligned on the board, and the board is very much aligned with the idea that Strava is extremely valuable and that Strava still has opportunity to go after that growth and that value.”

But the bulk of the company’s funding came via a $110 million Series F round nearly four years ago, and there isn’t much sense at the moment that the company is in a huge rush to pursue an exit. So should we expect another fundraise anytime soon?

“The balance sheet remains strong; we’ve been profitable from an adjusted EBITDA standpoint for more than four years already,” Martin said. “Our entire business top line, all the way down to profitability, has actually become much more successful in the last couple of months. So we don’t have any pressing need to raise capital.”